A survey of several articles on this topic.

Article 1. From Got Questions (https://www.gotquestions.org/intermediate-state.html)

The “intermediate state” is a theological concept that speculates regarding what kind of body, if any, believers in heaven have while they wait for their physical bodies to be resurrected. The Bible makes it clear that deceased believers are with the Lord (2 Corinthians 5:6-8; Philippians 1:23). The Bible also makes it clear that the resurrection of believers has not yet occurred, meaning that the bodies of deceased believers are still in the grave (1 Corinthians 15:50-54; 1 Thessalonians 4:13-17). So, the question of the intermediate state is whether believers in heaven are given temporary physical bodies until the resurrection, or whether believers in heaven exist in spiritual/non-corporeal form until the resurrection.

The Bible does not give a great amount of detail regarding the intermediate state. The only Scripture that specifically, but indirectly, speaks to the issue is Revelation 6:9, “… I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain because of the word of God and the testimony they had maintained.” In this verse John is given a vision of those who will be killed because of their faith during the end times. In this vision those believers who had been killed are under God’s altar in heaven and are described as “souls.” So, from this one verse, if there is a biblical answer for the intermediate state, it would seem that believers in heaven are in spiritual/non-corporeal form until the resurrection.

The heaven that ultimately awaits believers is the New Heavens and New Earth (Revelation 21-22). Heaven will indeed be a physical place. Our physical bodies will be resurrected and glorified, made perfectly fit for eternity on the New Earth. Currently, heaven is a spiritual realm. It would seem, then, that there would be no need for temporary physical bodies if believers are in a spiritual heaven. Whatever the intermediate state is, we can rest assured that believers in heaven are perfectly content, enjoying the glories of heaven and worshiping the majesty of the Lord.

Article 2. From Zondervan Academic: https://zondervanacademic.com/blog/intermediate-state

What happens after you die? In this post, we investigate the intermediate state—the state and the fate of each individual immediately after death but before the final resurrection.

The intermediate state is important for a couple of reasons: First, we need to wrestle with our own mortality. What will become of us when we die? Second, we must consider how we minister to the dying and bereaved. What hope do we offer them, and what details does the Bible give us for life beyond the grave?

Scripture has a great deal to teach us on this topic, and that’s what we’ll explore in this post, excerpted from Michael F. Bird’s Evangelical Theology.

Greek and Jewish understanding of death

The place of the dead is described with two mains words in Scripture: Sheol in the Old Testament and Hades in the New Testament. Unfortunately the Greek word hades is erroneously translated as “hell” in some English versions of the New Testament. The words Sheol and Hades refer to the abode of the dead, but not necessarily the final place of torment for the wicked.

In Hellenistic religious thought, Hades was the Greek god of the underworld, but Hades commonly referred to the realm of the underworld itself, where the souls of the dead endured a shadowy existence. Eventually the idea of postmortem rewards and punishments in Hades entered Greek thought, probably through Homer. Jewish views of the afterlife most likely developed independently of Greek thought, but Greek-speaking Jews did take on similar words and concepts from Greek and Roman views of Hades and the afterlife. The Hebrew concept of the place of the dead is called sheol; it is a place of darkness and gloom with a fading existence. The Hebrew word for sheol was translated as hades in the Septuagint, which explains the ten occurrences of hades in the New Testament (Matt 11:23; 16:18; Luke 10:15; 16:23; Acts 2:27, 31; Rev 1:18; 6:8; 20:13 – 14).

Jewish beliefs about a future day of judgment and the resurrection of the dead began to impact ideas about Sheol and Hades. Resurrection was a divine act of God bringing the dead in Hades back to life. Jewish writings are fairly consistent about Sheol and Hades as the place to which the dead depart (e.g., 2 Macc 6:23; 1 En. 102.5; 103.7; 2 Bar. 23.4), but the ultimate distinction between the righteous and the wicked at the final judgment could be anticipated during the temporary mode of existence in Hades. The best examples of this are 1 Enoch 22.1 – 14 and 4 Ezra 7.75 – 101, where the righteous and wicked are separated in Hades until the final judgment, with mixed fortunes for each group ahead of that day.

This provides the context for understanding several texts about “Hades” and the “imprisoned spirits” in Luke 16:19 – 31 and 1 Peter 3:19 – 20. The New Testament teaches that the kingdom of God will advance in such a way that the “gates of Hades/death” will not be able to break it. Moreover, the gates of Hades/death were thought to keep the dead imprisoned in its realm and only God can open the gates; yet the risen Lord says to John the Seer: “I am the Living One; I was dead, and now look, I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades”; this text means that he has acquired the divine power to release people from the realm of the dead.

What the Gospels say about the intermediate state

How the parable of the rich man and Lazarus depicts the afterlife

A number of texts from Luke provide information about a possible intermediate state. The most controversial is the parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:19–31:

There was a rich man who was dressed in purple and fine linen and lived in luxury every day. At his gate was laid a beggar named Lazarus, covered with sores and longing to eat what fell from the rich man’s table. Even the dogs came and licked his sores.

The time came when the beggar died and the angels carried him to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried. In Hades, where he was in torment, he looked up and saw Abraham far away, with Lazarus by his side. So he called to him, “Father Abraham, have pity on me and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, because I am in agony in this fire.”

But Abraham replied, “Son, remember that in your lifetime you received your good things, while Lazarus received bad things, but now he is comforted here and you are in agony. And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been set in place, so that those who want to go from here to you cannot, nor can anyone cross over from there to us.”

He answered, “Then I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my family, for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment.

Abraham replied, “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them.”

“No, father Abraham,” he said, “but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent.”

He said to him, “If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.”

The key thing to remember about this passage is that it is a fictive narrative designed to reinforce the point made in Luke 16:14 – 18 about the terrible dangers of the love of money. It is the ancient equivalent to vignettes about “St. Peter’s Gate” or the “Pearly Gates,” where the meaning is moral rather than literal. So although this parable refers to the intermediate state, personal eschatology is not its main point.

With that caveat in mind, we can conclude the following:

- The story corresponds with what we saw above, where the concept of Hades developed in Jewish thought so that the division of the final judgment between the righteous and the wicked was already anticipated in the abode of the dead.

- It also reflects the view found in the Testament of Abraham 20.14, which refers to a “paradise” in the afterlife where there is the “bosom of Abraham,” and how Abraham’s descendants there enjoy “peace and rejoicing and life unending.”

Luke’s parable is a hyperbolic depiction of an existence in the afterlife that affirms an intermediate state in Hades prior to the final resurrection, but its major concern is Abraham’s refusal to the rich man’s request to send a messenger, and so it highlights the inexcusable behavior of the rich and the penalty that awaits them.

Jesus’ remarks on the cross about the afterlife

Also in the gospel of Luke, there is a curious remark uttered by Jesus on the cross. When one of the bandits crucified with Jesus asks him, “Remember me when you come into your kingdom” (Luke 23:42), Jesus replies with the promise, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise” (23:43).

The saying is problematic because the other two appearances of paradeisos in the New Testament both refer to heaven (2 Cor 12:4; Rev 2:7). Yet Jesus did not go to heaven between the cross and resurrection. We find this clearly in the Johannine resurrection narrative, where the risen Jesus tells Mary: “Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my brothers and tell them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God’ ” (John 20:17).

So if Jesus was not in “heaven,” then where did he go? What is this “paradise” he promised the bandit?

Most likely, “paradise” here denotes the intermediate state and is another way of referring to Hades. This comports with the biblical teaching that when Jesus died, he went to the waiting place of the dead (Acts 2:27, 31; 1 Pet 3:19 – 21). The Greek word paradeisos was a Persian loanword that denoted an enclosed park surrounded by a wall. It was known to Hellenistic authors like Xenophon and adopted by Jewish authors to refer to Eden in the creation account in Genesis 2:8 – 10, 16 (LXX). It was also used to describe the future state so that the future city of Jerusalem will be like the garden of Eden (Ezek 36:35; cf. 28:13; 31:8 – 9). In subsequent Jewish thought, paradise also referred to the present abode of departed patriarchs, the elect, and the righteous (1 En. 60.7 – 8, 23; 61.12; 70.4; 2 En. 8.1 – 8; 9.1; 42.3; Apoc. Mos. 37.5). Paradise here is an intermediate state that is neither heaven nor hell; it is the waiting place of the dead, the blissful location within sheol or hades.

What the stoning of Stephen tells us about the afterlife

Shifting to Luke’s second volume, the Acts of the Apostles, Stephen is stoned for his testimony to Jesus’ exaltation to the right hand of God (Acts 7:55 – 60). As he is bludgeoned with stones, Stephen exclaims, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit’” (7:59). This mirrors the words of Jesus himself at his crucifixion, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46). It is christologically significant that while the Lucan Jesus prays to the Father to receive his spirit at his crucifixion, Stephen prays that Jesus would receive him beyond his martyrdom.

What Luke presents to his readers is not a platonizing of the afterlife; more likely these three texts (Luke 16:19 – 31; 23:43, 46; Acts 7:55 – 60) exhibit belief in an intermediate state located in Hades before the resurrection and then in heaven after the resurrection.

What Paul says about the intermediate state

References to an intermediate state were not a mainstay of Paul’s eschatological teachings that focused primarily on Christ’s parousia, the resurrection, and the final judgment. Information about an intermediate state must be inferred from Paul’s remarks elsewhere. Paul writes to the Philippians from Ephesus about his imprisonment and possible execution:

I eagerly expect and hope that I will in no way be ashamed, but will have sufficient courage so that now as always Christ will be exalted in my body, whether by life or by death. For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain. If I am to go on living in the body, this will mean fruitful labor for me. Yet what shall I choose? I do not know! I am torn between the two: I desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far; but it is more necessary for you that I remain in the body. (Phil 1:20 – 24)

Paul contrasts “living in the body” with departing to “be with Christ, which is better by far.” Paul provides no data about the nature of this state, where it takes place, or what form he exists in there, and we can only assume that death entails a removal from his body and transportation to instant intimacy with the Savior.

The place where Paul discourses specifically about the postmortem fate of the individual, starting with himself, is 2 Corinthians 5:1 – 10:

For we know that if the earthly tent we live in is destroyed, we have a building from God, an eternal house in heaven, not built by human hands. Meanwhile we groan, longing to be clothed instead with our heavenly dwelling, because when we are clothed, we will not be found naked. For while we are in this tent, we groan and are burdened, because we do not wish to be unclothed but to be clothed instead with our heavenly dwelling, so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life. Now the one who has fashioned us for this very purpose is God, who has given us the Spirit as a deposit, guaranteeing what is to come.

Therefore we are always confident and know that as long as we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord. For we live by faith, not by sight. We are confident, I say, and would prefer to be away from the body and at home with the Lord. So we make it our goal to please him, whether we are at home in the body or away from it. For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, that everyone may receive what is due them for the things done while in the body, whether good or bad. (italics added)

It is often alleged that in these verses Paul has abandoned the apocalyptic eschatology of 1 Corinthians 15, with its future resurrection of the body, for a resurrection into a spiritual body into God’s presence immediately after death. But this is hardly likely since Paul’s reference to “we know” (5:1) introduces a rehearsed doctrine rather than a newly fashioned one. Second, Paul has intimated earlier in the letter his continued affirmation of the resurrection (1:9 – 10; 4:14) and affirms it again a few sentences later (5:15). Third, 1 Corinthians 15 and 2 Corinthians 5 share a lot of vocabulary, such as “unclothed” and “earthly.” Paul’s teaching on the future remains consistent, though in 2 Corinthians 5 he does begin to talk about the immediate postmortem fate of the individual, starting with himself.

Paul had intimated an interval between death and resurrection that was a bodiless one (1 Cor 15:35 – 38) and a temporary state (15:32 – 44). Now as he faces the expectation of death ahead of the parousia, he turns his mind to what lies in store for him. If Paul expected to receive a spiritual resurrection body after his death, it leads one to wonder why he would still anticipate the Lord’s return in the future since resurrection and parousia have been consistently bound together in his eschatology across the Thessalonian and Corinthian correspondences and also later in Philippians and Romans.

What Paul appears to envisage immediately upon death is not a spiritual resurrection, but a future spiritual mode of existence that is transcendent, yet not fully actualized until the parousia. There is a transition from the sarkic (fleshly) and somatic (bodily) form of existence into a heavenly dwelling in the company of the Lord, characterized by a heightened form of interpersonal communion with Christ.

Yet this state is clearly something that is prior to Christ’s parousia and the resurrection because it is ahead of the judgment of believers when their resurrection will take place. Paul hopes to please the Lord in both his bodily state and in his heavenly dwelling, knowing that he will stand before Christ at the final judgment. In any case, the promise of the Spirit and the object of faith is such that he looks forward to leaving his body, imagining a time away from the body in this eternal dwelling, and then presumably being raised to stand at the final judgment.

What Revelation says about the intermediate state

The book of Revelation focuses attention on the events leading up to the final state of a new heaven and a new earth (Rev 22:1 – 5). Still, John makes some comments about a possible intermediate state for believers after death and before their resurrection.

The state of the martyrs according to Revelation

First, when John the Seer refers to the state of the martyrs, it is clear that they exist in a heavenly dimension that is at once both blissful and yet not entirely satisfying.

For example, see Revelation 6:9–11:

When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain because of the word of God and the testimony they had maintained. They called out in a loud voice, “How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?” Then each of them was given a white robe, and they were told to wait a little longer, until the full number of their fellow servants and brothers and sisters were killed just as they had been.

And here’s Revelation 7:13–17:

Then one of the elders asked me, “These in white robes — who are they, and where did they come from?” I answered, “Sir, you know.” And he said, “These are they who have come out of the great tribulation; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb. Therefore, “they are before the throne of God and serve him day and night in his temple; and he who sits on the throne will shelter them with his presence. Never again will they hunger; never again will they thirst. The sun will not beat down on them, nor any scorching heat. For the Lamb at the center of the throne will be their shepherd; he will lead them to springs of living water. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.”

In Revelation 6, the martyrs cry out for vindication and look forward to the judgment and wrath that are set to follow upon those who mistreated and murdered them. In Revelation 7, the martyrs enter into the presence of the throne room of heaven and engage in heavenly worship and enjoy heavenly peace, and they are shepherded by the Lamb, who comforts them. This penultimate stage depicts departed saints as being in the presence of God in heaven.

Are Hades and hell the same thing?

Another thing to note from Revelation is the relationship between “Hades” and “hell.” In Revelation, Hades is closely related to “death” and thus stands for the waiting place of the dead rather than the final place of the condemned (Rev 1:18; 6:8; 20:13 – 14). Though the Greek word for “hell” (gehenna) does not occur in Revelation, there is mention of a “lake of fire/burning sulfur” that amounts to the same thing (19:20; 20:10, 14 – 15; 21:8). Note that “death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death” (20:14). That is, Hades is thrown into hell. That would mean that no one is in hell yet, and the contents of Hades will be dumped into hell at the final judgment.

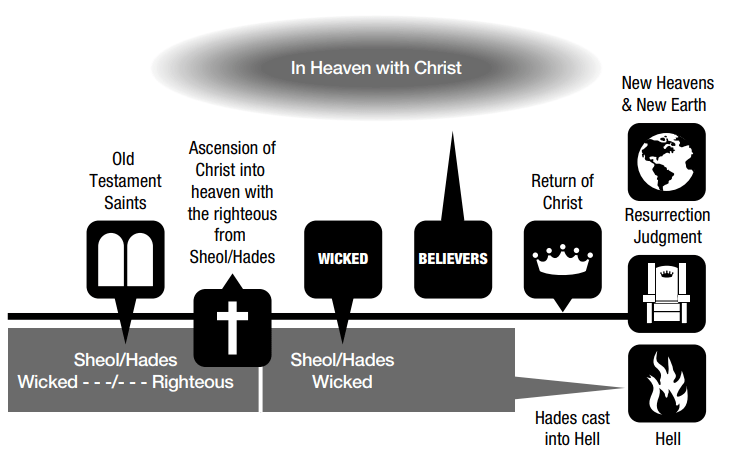

In view of all of this, I would represent the intermediate state as follows:

Prior to Christ’s ascension, all who died descended to Sheol/Hades, which was divided into two parts, one for the wicked and one for the righteous.- At Christ’s ascension, he went into heaven and took with him all of the saints in the paradisal part of Sheol/Hades, while the wicked remain in Sheol/Hades, waiting for judgment.

- Upon death new covenant believers go to be with Christ in heaven ahead of the general resurrection, while the wicked descend to Sheol/Hades waiting for judgment.

- Eventually Sheol/Hades will be thrown into hell and all believers will share in the new heavens and new earth.

It’s important to note that an affirmation of a future resurrection does not demand that there is no conscious existence in a nonbodied, postmortem state ahead of the resurrection. When Paul dies, he intends to be with Christ, which is better than his current bodily existence (Phil 1:23); yet he also thinks of the immediate postmortem state as something temporary, like a car on loan from a mechanic, waiting for the original vehicle to be renewed (cf. 1 Cor 15:35 – 38). So it seems that upon death, the separation of body and soul is both blessing and a bummer, something enjoyable but also somewhat ephemeral. The unity of the material and immaterial parts of one’s being are the norm, but death ruptures that norm ahead of the resurrection. Yet, despite the awkward disunity of body and soul at death, believers still enjoy God’s presence and look forward to the day when they will be raised in a psychosomatic unity of body and soul in God’s everlasting kingdom.

Christ is the place of rest

It is difficult to plot the exact place and type of existence in the intermediate state. No text, save perhaps 2 Corinthians 5, discourses on it at length. But overall it seems that Joachim Jeremias was correct when he writes: “The New Testament consistently represents fellowship with Christ after death as the distinctively Chris tian view of the intermediate state.”

The intermediate state has to be articulated primarily in christological terms. Paul is clear that one departs to be with Christ (Phil 1:23), and according to John the Evangelist, where Christ is, there believers will also be (John 14:3). For nothing, not even death or demons, will separate believers from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord (Rom 8:38 – 39). The intermediate state brings fellowship with Christ, and in him we find also the continued fellowship of believers ahead of the final consummation (Heb 12:23). Death does not eradicate the believer’s union with Christ or communion with fellow believers. Whatever life is ahead in the eschatological future, interim and final, it can only be a “life in Christ.”

— adapted from Michael F. Bird’s Evangelical Theology.

Article 3. From Bible.org https://bible.org/seriespage/2-intermediate-state

What is the intermediate state? This refers to “the conscious existence of people between physical death and the resurrection of the body.”1 This is important to consider because some believe in something called soul sleep which simply means people’s souls will rest in an unconscious state or temporarily cease to exist between the death of the body and their resurrection to eternal life or eternal judgment. This view is taken from verses that describe death as sleep (John 11:11-14, 1 Cor 11:30 NIV). However, Scripture is very clear that people will be conscious in the intermediate state—either suffering in hell or enjoying the blessings of heaven (Lk 16:22-26).

With that said, Scripture also teaches that the current heaven and hell are only temporary holding places, and the inhabitants will eventually reside in the new heaven and earth or the lake of fire. Revelation 21:1-4 describes the new heaven and earth that believers will eternally reside in. It says,

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and earth had ceased to exist, and the sea existed no more. And I saw the holy city—the new Jerusalem—descending out of heaven from God, made ready like a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying: “Look! The residence of God is among human beings. He will live among them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death will not exist any more—or mourning, or crying, or pain, for the former things have ceased to exist.”

Likewise, Revelation 20:12b-15 says this about the lake of fire, which the current hell (or hades) will be thrown into:

So the dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to their deeds. The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and Death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and each one was judged according to his deeds. Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death—the lake of fire. If anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, that person was thrown into the lake of fire.

The Intermediate Heaven

There is not much information given in Scripture about the intermediate heaven, but there is enough for one to develop a theology of it and avoid confusing the temporary state with the eternal state. For example, often when thinking of the present heaven, people overemphasize it by considering it our final home; however, it is not. Second Peter 3:13 says, “But, according to his promise, we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth, in which righteousness truly resides.” Also, in Revelation 5:10, heaven’s inhabitants say this about the redeemed, “You have appointed them as a kingdom and priests to serve our God, and they will reign on the earth.” It was originally God’s will for people to rule under him on the earth, and the redeemed will do that in the eternal state, while also having access to heaven which in its final form will reside on the earth (Rev 21:2-3, 10).

Another misunderstanding about the intermediate heaven is that people often believe that it shares the same promises of the final form of heaven, such as there being no more “mourning” or “crying” there (Rev 21:4). This is not necessarily true. For example, Revelation 6:9-11 describes the souls of those who had been martyred during the tribulation and their petitions to God. It says,

Now when the Lamb opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been violently killed because of the word of God and because of the testimony they had given. They cried out with a loud voice, “How long, Sovereign Master, holy and true, before you judge those who live on the earth and avenge our blood?” Each of them was given a long white robe and they were told to rest for a little longer, until the full number was reached of both their fellow servants and their brothers who were going to be killed just as they had been.

A few things can be discerned from this description of the souls in the intermediate heaven. (1) They were aware of what was happening on the earth and (2) were also mourning those events. Though some think believers are unaware of the events on the earth because it would take away their happiness, that does not appear to be the case. These martyred believers are mourning before the Lord and asking when he would judge those on the earth. Since in the intermediate heaven believers are more like God, they not only rejoice over righteousness—such as when a person accepts Christ (Lk 15:7)—they also mourn over sin and desire justice, as our God does. Psalm 7:11 says, “God is a just judge; he is angry throughout the day.” No doubt, believers in heaven, who appear to be aware of the events on the earth, also share God’s anger and mourning over sin. Another potential evidence that believers are aware of what is happening on the earth is Hebrews 12:1. It says, “Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, we must get rid of every weight and the sin that clings so closely, and run with endurance the race set out for us.” The author pictures an amphitheater with the great heroes of the past (spoken of in Hebrews 11) watching us and probably cheering us on as we run. Certainly, this fits the picture of heaven’s inhabitants rejoicing over the salvation of one soul (Lk 15:7). (3) Another aspect we can discern about the souls of the righteous in the intermediate heaven is that they are not just aware of events on the earth, but they also are aware of one another, including their past suffering. In 1 Corinthians 13:12, Paul said this about heaven: “For now we see in a mirror indirectly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know in part, but then I will know fully, just as I have been fully known.” This may specifically refer to the eternal state, but it also probably has ramifications for the intermediate heaven. In heaven, it seems people will have a fuller knowledge of things, including God and other people. Christ may have pictured this in Luke 16:9 when he said, “And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by how you use worldly wealth, so that when it runs out you will be welcomed into the eternal homes.” In the verse, Christ described believers who gave generously while on earth being welcomed into “eternal homes” by friends who were blessed (and possibly saved) through their giving. These friends in heaven apparently had full knowledge of others’ generous giving on earth and how it affected them spiritually. In heaven, we will have a fuller knowledge of ourselves, others, and God. (4) Finally, we can also learn from the description of martyred saints in Revelation 6 that believers in the intermediate heaven might have some type of spirit body. They are given white robes to wear (6:11). Clearly, they do not have resurrected bodies yet, but they appear to have some type of tangible form that can wear a robe.

Likewise, another misconception about the intermediate heaven is that people often believe nothing sinful can enter it, as will be true of the new heaven (Rev 22:14-15). However, it must be remembered that there was a fall in heaven before there was a fall on earth (Rev 12:4). Satan and one-third of the angels rebelled against God, and though they were cast out, they still have access to heaven. In the book of Job, Satan is shown appearing before God and the angels (Job 1:6 and 2:1). Also, in 1 Kings 22:19-23, there is a similar scenario. As King Ahab and Jehoshaphat prepare to go to battle, an assembly of angels appears before God, and a lying spirit volunteers to go out and deceive those kings so they will go to war and Ahab will die. Finally, in Revelation 12, which will happen at some point during the tribulation period, Satan and his demonic angels will stage a final war against God and his angels and be permanently cast out of heaven. Revelation 12:7-9 says:

Then war broke out in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. But the dragon was not strong enough to prevail, so there was no longer any place left in heaven for him and his angels. So that huge dragon—the ancient serpent, the one called the devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world—was thrown down to the earth, and his angels along with him.

No doubt, because of Satan’s rebellion, Scripture says that to God the intermediate heaven is not pure. In Job 15:15, Eliphaz says, “If God places no trust in his holy ones, if even the heavens are not pure in his eyes.” Though Eliphaz, Job’s misguided friend, said this, it appears to be correct. In Hebrews 9:22-24, in the context of the earthly tabernacle and its articles needing to be purified with the blood, the author says the heavenly sanctuary needed to be purified by Christ’s blood:

Indeed according to the law almost everything was purified with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness. So it was necessary for the sketches of the things in heaven to be purified with these sacrifices, but the heavenly things themselves required better sacrifices than these. For Christ did not enter a sanctuary made with hands—the representation of the true sanctuary—but into heaven itself, and he appears now in God’s presence for us.

Surely, the intermediate heaven is not perfect before God, which is why Satan and his angels have access to it. It needed to be purified by Christ’s blood and will need to be defended against Satan’s attacks (Rev 12:7-9).

The greatest aspect of the intermediate heaven, which will continue in its final state, is unbroken access to God (cf. Rev 22:4). In 2 Corinthians 5:8, Paul said this: “Thus we are full of courage and would prefer to be away from the body and at home with the Lord.” In addition, in Philippians 1:23, Paul said this about dying, “I have a desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far.” Surely, as the Psalmist said, there is “absolute joy” in God’s presence (Ps 16:11). There, believers will “rest from their hard work” (Rev 14:13) in the sense of the burdens of their labor, as they enjoy God and serve him.

Though the intermediate heaven will bring peace, joy, and rest from labor for believers, it is not their final home. Since heaven has been tainted by sin like earth has, God will renew them both, so believers may inhabit and serve God eternally there. Second Peter 3:10-13 says,

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief; when it comes, the heavens will disappear with a horrific noise, and the celestial bodies will melt away in a blaze, and the earth and every deed done on it will be laid bare. Since all these things are to melt away in this manner, what sort of people must we be, conducting our lives in holiness and godliness, while waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God? Because of this day, the heavens will be burned up and dissolve, and the celestial bodies will melt away in a blaze! But, according to his promise, we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth, in which righteousness truly resides.

We will consider the new heaven in greater detail when studying cosmic eschatology later in this book.

Paradise or Abraham’s Side

With all that said, many believe that before Christ’s resurrection, the righteous did not reside in heaven but in paradise or Abraham’s bosom in a place called sheol, which was in the center of the earth. Sheol is a general term used in the Old Testament, which can be translated as “grave” or “realm of the dead” (Gen 37:35, Ps 16:10, 86:13, Ecc 9:10, Hosea 13:14, Job 14:13, 26:6, etc.).2 When referring to the realm of the dead, it is believed to have had two compartments—one for the righteous (Abraham’s side) and one for the unrighteous (hell). Between these two places was a “great chasm” which no one could cross (Lk 16:26). This great chasm indicated that after death, a person’s fate was sealed and could not be changed.3 These two places in sheol are referred to in Christ’s story about a poor man named Lazarus and a rich man. In Luke 16:22-26, Christ said:

Now the poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried. And in hell, as he was in torment, he looked up and saw Abraham far off with Lazarus at his side. So he called out, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, because I am in anguish in this fire.’ But Abraham said, ‘Child, remember that in your lifetime you received your good things and Lazarus likewise bad things, but now he is comforted here and you are in anguish. Besides all this, a great chasm has been fixed between us, so that those who want to cross over from here to you cannot do so, and no one can cross from there to us.’

This story gives strong support for believers going to paradise, or Abraham’s side, before Christ’s resurrection. Those who reject this view say Christ’s story was a parable—a fictional story given to teach a spiritual principle. However, what makes this story unique is that Christ uses names, which never happens in parables. Christ speaks of Abraham (a real person) and a poor man named Lazarus. Using the names of real people instead of, for example, the “older brother” and “younger brother” in the parable of the prodigal son gives credence that the story was an actual event, including paradise being within sheol.

Apparently, Christ visited paradise, which was in sheol, after his death. In Luke 23:43, Christ said, “I tell you the truth, today you will be with me in paradise.” Paradise, and the believers in it, were most likely moved to heaven after Christ’s resurrection (cf. 2 Cor 12:2-4). Ephesians 4:8-9 (NIV) may refer to this when it says, “This is why it says: ‘When he ascended on high, he took many captives and gave gifts to his people.’ (What does ‘he ascended’ mean except that he also descended to the lower, earthly regions?” When ancient kings defeated an enemy, they would not only take enemy prisoners and lead them through their cities in a victory parade as trophies, but also commonly recapture their own soldiers, who were previously taken as prisoners.4 When Christ ascended from sheol to heaven, he took his people to heaven with him. This was the view of the early church. John MacArthur said this about the early church’s belief:

Early church dogma taught that the righteous dead of the Old Testament could not be taken into the fullness of God’s presence until Christ had purchased their redemption on the cross, and that they had waited in this place for His victory on that day. Figuratively speaking, the early church Fathers said that, after announcing His triumph over demons in one part of Sheol, He then opened the doors of another part of Sheol to release those godly captives. Like the victorious kings of old, He recaptured the captives and liberated them, and henceforth they would live in heaven as eternally free sons of God.5

Intermediate Hell

In the same way that believers reside in the intermediate heaven awaiting their resurrection and their entering the new heaven and earth, unbelievers reside in the intermediate hell, often called hades. It is a place of temporary conscious torment for the wicked. As pictured in Jesus’ story about Lazarus and the rich man, which was previously discussed (Lk 16:22-26), the rich man in hell remembered Lazarus, desired for his brothers to not come to the same place of torment, and also desired for a drip of water to cool his tongue, because he was suffering in the flames. In hell, people will consciously suffer for their sins and eventually be resurrected to be judged by Christ for their sins and then thrown into the lake of fire to suffer eternally (Rev 20:12-15). The final form of hell will be discussed more thoroughly when considering cosmic eschatology later in this book.

Conclusion

The intermediate state is where deceased unbelievers and believers temporarily reside. Unbelievers currently reside in a place of conscious suffering called hell, and believers reside in a place of conscious blessing called the intermediate heaven. Each awaits their destiny in the eternal state, either in the lake of fire or the new heaven (Rev 20:15) and the new earth (Rev 21:1).

Article 4. From Bible Gateway – (https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/encyclopedia-of-the-bible/Intermediate-State)

NTERMEDIATE STATE. This expression commonly designates that realm or condition in which the soul exists between the decease of the body and the resurrection. Although the Bible says little about the state of the dead, it is clear even from the OT that the human personality survives death, whereas the doctrine of immortality is a firm tenet of NT faith. Differences of opinion regarding the intermediate state relate to its nature: whether or not it is purgatorial in function; whether or not the human spirit has a chance to repent, and whether or not the soul is conscious of its environment. Regarding the state of the dead, the Bible required bodily resurrection as the goal of individual eschatology. Man does not consist of separate units of body, mind, or soul (spirit), but is a dynamic integrated personality of which these are aspects. Immortality, therefore, does not mean endless existence so much as freedom from death (1 Cor 15:53) and from corruption (Rom 2:7). In Christ, men will exchange their mortality for immortality at the resurrection (1 Cor 15:53, 54). In OT belief, the human personality (nepeš) went at death to Sheol, a lowly region of darkness and silence (Ps 86:13; Prov 15:24; Ezek 26:20; Job 10:22). The dead, who were gathered in tribes (Ezek 32:17-32), received the dying (Isa 14:9, 10). Although Sheol was not so much the realm as the style of the dead, it was not life, since that could only flourish in the divine presence (Ps 16:10), to which God’s people would ultimately be brought (16:9-11; 73:24; Job 19:25, 26). The Gr. “Hades,” rendered “hell” and “grave” in the NT (Matt 11:23; Luke 10:15; Acts 2:27; 1 Cor 15:55 KJV, etc.) is the equivalent of Sheol, and takes its place with the other concepts of life after death, such as paradise (see Eschatology). NT thought about the intermediate state was influenced in the intertestamental period by Pharisaic views on Sheol, the resurrection, and the judgment. In the pre-Christian period, Sheol was regarded not as the permanent home, but only the intermediate place for the departed spirits. It was the intermediate abode of the righteous only, who would leave it later on at the resurrection (Pss Sol 14:6, 7; 2 Macc 7:9; 14:46). Although OT thought saw little connection between God and Sheol, 2 Maccabees 12:43-45 records Judas Maccabeus as praying that his fallen soldiers would be released from their sins there to prepare them for the resurrection. Enoch 22 states that Sheol was divided into three separate places, one for the righteous, another for the wicked who died before divine retribution overtook them, and a third for the wicked who were punished adequately while still alive. In 4 Ezra 7:95; 2 Baruch 21:23ff., the souls of the wicked went straight to Sheol, whereas the righteous ascended to heavenly chambers to enjoy rest and quietness under the protection of angels before being resurrected. All interestamental eschatology was founded upon a “three-storied universe,” with heaven (or a series of heavens) being the divine abode above the earth, and Sheol (the place of departed spirits) or Gehenna (the place where the wicked were punished) as an underworld. Occasionally, Sheol was regarded as the place of punishment also. The soul of Adam ascended at death to paradise, the third of seven heavens (see Paradise). The term “paradise” originally meant a “park” or “enclosed garden,” and for pre-Christian Judaism it designated the original Garden of Eden as either the eternal abode of the righteo us or their locale prior to the resurrection. In the NT, the parabolic reference to “Abraham’s bosom” (Luke 16:22-31) made use of such thought, but was prob. not intended to teach anything about the state of the dead. If Paul’s experience was that of a visit to paradise where he received a revelation (2 Cor 12:1-4), it appears that he thought of the righteous dead as already living in paradise with the Lord (cf. 2 Cor 5:8; Phil 1:23). On the cross, Christ promised the penitent thief an abode in paradise (Luke 23:43), which indicates that the righteous entered paradise at death. The Book of Revelation also teaches clearly that at least some righteous enter a celestial abode after death but before the final resurrection (Rev 6:9-11; 7:9-17).

Intertestamental beliefs regarding the intermediate state were closely linked with the concept of physical resurrection, a doctrine espoused by the Pharisees but denied by the Sadducees. The resurrection of the dead was anticipated in a few OT passages (Isa 25:8; 26:19; Dan 12:2), and was encouraged both by speculation on the nature of the intermediate state in Sheol and the joys of the coming Messianic age. In the light of the latter in particular, it was only just that the righteous departed should share the joys of divine rule, and the wicked dead be punished correspondingly. The concept of the physical resurrection was a necessary accompaniment to such thought, and in most instances the soul was imagined as coming from Sheol or some other intermediate state to rejoin the body buried on earth previously. Under Pharisaic influence the doctrine of resurrection developed certain coarse, materialistic features (see Resurrection) that were typical of their shallow beliefs.

People came to assume the existence of another intermediate state known as Purgatory, which was frequently confused with Sheol (2 Macc 12:39-45). The Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches proclaimed the existence of a place of temporal punishment in the intermediate realm designated “purgatory,” in which all who died in a state of ecclesiastical grace must undergo a period of purifying so as to make them perfect before God. Thus the bulk of baptized people dying in fellowship with the church would have to pass through purgatory before being translated to heaven. Cultic prescriptions for the duration of the experience vary in degree, as do the sufferings of those thought to be in this state. Monetary and other gifts to the church, prayers, and acts of devotion, are held to shorten or even eliminate the stay of the individual soul in purgatory. This view has no OT or NT support, runs counter to the Biblical doctrine of a final judgment, and is flatly contradicted by a passage which the Roman Catholics regard as Scripture (Wisd Sol 3:1-4).

In the NT, other expressions than “paradise” refer to the existence of the righteous after death (Mark 12:18-27; Luke 16:9, 19-31; Rev 6:9-11, etc.), and whereas much of the language concerning the state of the dead is symbolic, it does at least enlarge the OT revelation that death does not terminate individual existence. It is clear that the saints live on after death in glory in the divine presence realizing the goal of redemption in Christ (2 Cor 5:8; Phil 1:23; Rev 14:13). Because the total man is saved, references to the “salvation of your souls” (1 Pet 1:9; James 1:21) do not contemplate the salvation of the “soul” apart from the “body.” Describing the intermediate state as “rest” (cf. Heb 4:10) does not mean that those present in it are indolent or inactive, but are satisfied by the joy of accomplishment. Even for the righteous, the intermediate state would seem to be one of imperfection, partly because the spirit is without a bodily manifestation and partly because the joys of heaven are not forthcoming for the saints until after the Second Coming of Christ and the final judgment. Thus, the blessings of the intermediate state presage future divine blessings. Life in the resurrection body in heaven marks the final stage of individual salvation.

Bibliography G. Vos, The Pauline Eschatology (1952 ed.); G. R. Beasley-Murray, Jesus and the Future (1954); E. Brunner, Eternal Hope (1954); J. E. Fison, The Christian Hope (1954); R. Summers, The Life Beyond (1959).

Article 5. From Christianity.com – https://www.christianity.com/wiki/christian-terms/intermediate-state.html

The term intermediate state helps Christians discuss a sticky question: what happens between when we die and the final resurrection?

There is more to life after death than being in God’s presence. We are awaiting the new heavens and the new earth that come at the end of time. The American church often thinks of eternity as a disembodied Spirit, but the Scriptures offer a much richer picture. The time between our death and Christ’s final judgment is known as the intermediate state. Paul refers to this as both being in the presence of the Lord and falling asleep.

What Is the Intermediate State?

The intermediate state refers to the destination of the human soul after death but before Christ’s return. All souls end up either in paradise with God or in hell apart from him until the final judgment. This vision is seen in Revelation 4-6, where people from every nation, tribe, people, and language worship God. Some view the intermediate state as the soul sleeping until the day of judgment.

Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox Christians have developed varying views on the intermediate state over the centuries.

What Does the Bible Say about the Intermediate State?

Paul says in Philippians 1:23 that when he dies he will be with Christ. This means that our souls immediately go to be with Christ. If Paul thought he would cease to be conscious after death he likely would not have seen it as beneficial. Elsewhere, he says believers have “fallen asleep,” but this is in a bodily sense, not a spiritual one.

There is more to life after death than being in God’s presence. We are awaiting the new heavens and the new earth that come at the end of time. The American church often thinks of eternity as a disembodied Spirit, but the Scriptures offer a much richer picture. The time between our death and Christ’s final judgment is known as the intermediate state. Paul refers to this as both being in the presence of the Lord and falling asleep.

What Is the Intermediate State?

The intermediate state refers to the destination of the human soul after death but before Christ’s return. All souls end up either in paradise with God or in hell apart from him until the final judgment. This vision is seen in Revelation 4-6, where people from every nation, tribe, people, and language worship God. Some view the intermediate state as the soul sleeping until the day of judgment.

Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox Christians have developed varying views on the intermediate state over the centuries.

What Does the Bible Say about the Intermediate State?

Paul says in Philippians 1:23 that when he dies he will be with Christ. This means that our souls immediately go to be with Christ. If Paul thought he would cease to be conscious after death he likely would not have seen it as beneficial. Elsewhere, he says believers have “fallen asleep,” but this is in a bodily sense, not a spiritual one.

What Was the Ancient Jewish View of the Intermediate State?

The Jewish view of the afterlife was known as Sheol. Until the intertestamental period it was believed that all souls would end up in Sheol for eternity. People in Sheol did not praise God. David makes this clear when he says in Psalm 6, “In death there is no remembrance of you, who in Sheol can give you praise?”

The view that souls would be resurrected at the end of history gained popularity after the Babylonian exile. This shows up in a prophecy in Daniel, which is the only explicit reference to the resurrection in the Hebrew Bible. This dearth of evidence led the Sadducees of Jesus’ day to reject the resurrection and therefore the intermediate state altogether.

What Are the Different Christian Views on the Intermediate State?

Traditional Protestant View

The belief that Christians enter the immediate presence of Christ upon death is central in many Protestant traditions. This view suggests that upon physical death, the soul of a believer is taken directly into a conscious, blissful fellowship with Christ in heaven. This immediate transition to heaven is seen as a temporary state until the final resurrection and judgment, during which believers will be reunited with glorified, resurrected bodies.

This belief aligns with several passages in the New Testament, such as Paul’s declaration, “To be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8) and his desire “to depart and be with Christ, which is far better” (Philippians 1:23).

While in the presence of Christ, believers will experience comfort, joy, and peace, but they do not yet have their physical, resurrected bodies. The full bodily resurrection and the final judgment occur at Christ’s second coming, marking the complete fulfillment of salvation and the restoration of all creation.

Roman Catholic View

The Catholic view of the intermediate State has been explained in detail by Dante Alighieri in his three epic poems, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (also known collectively as the Divine Comedy). The first and last are the views of heaven and hell that Protestants share. The third is what distinguishes the Catholic view from other forms of Christianity. In Catholic doctrine, Purgatory is the place where humans work off unconfessed venial sins between their death and the return of Christ.

Roman Catholics use verses like 1 Corinthians 3:13 to justify the doctrine of purgatory. This verse says that the quality of each person’s work will be seen on the Day of Christ. Protestant theologians maintain that the Day of Christ refers to judgment day, not to the time of a believer’s death. Therefore there is no basis for purgatory as a destination for souls. It is also worth noting that the text says the fire, punishment, and rewards are for the teacher.

Catholics hold certain deuterocanonical books of the Bible on the same level as other scriptures, contributing to their views on the intermediate state. The deuterocanonical 2 Maccabees provides the basis many Catholics use for purgatory. 2 Maccabees 12:44-45 says it is good to pray for the dead so that they may be freed from their sins. 2 Maccabees was written before Christ’s birth, meaning the writer believed there was no hope of permanent freedom from sin. The writers would have believed the recipients of prayer were in Sheol. Now, in Christ, the old covenant has been fulfilled. Hebrews 9:8-9 says that gifts and sacrifices of the old covenant could not perfect the sacrifice of the worshipers. Hebrews 10:14 says that “by one offering he has perfected for all time those who are made holy.” The doctrine of purgatory is still operating under old covenant principles that state that humans must work in order to be forgiven.

Purgatory has problems when examined in light of scripture. The Bible teaches that Jesus’ death credited his righteousness to us. 2 Corinthians 5:21 is also known as the great exchange. This means that Christ took on our sin, and we were credited his righteousness in God’s sight. This is known as the imputed righteousness of Christ. Purgatory says that believers need to work off their own sins because they are not yet worthy to be in God’s presence.

Saints, meanwhile, died in a state of grace, and enter directly into paradise. There they behold Jesus and go before him to intercede for the people on earth. Catholics believe that saints can hear their prayers from heaven, and intercede before Jesus on their behalf. According to the Catechism, “Just as Christian communion among our fellow pilgrims brings us closer to Christ, so our communion with the saints joins us to Christ, from whom as from its fountain and head, issues all grace, and the life of the People of God itself.”

There is no scriptural evidence that saints are able to hear our prayers from heaven. This is another example of the different authority the Catholic Church has. The Roman Catholic Church gets its doctrine from three places, the Bible, Tradition, and the Pope. This view of saints as intercessors became prominent over the years because people had trouble relating with Jesus as a mediator and friend.

Eastern Orthodox View

Eastern Orthodoxy also holds the idea that the soul is conscious after death. Orthodox theologians often cite Justin Martyr, who wrote the following:

“For let even necromancy, and the divinations you practice by immaculate children, and the evoking of departed human souls, and those who are called among the magi, Dream-senders and Assistant-spirits (Familiars), and all that is done by those who are skilled in such matters —let these persuade you that even after death souls are in a state of sensation.” (First Apology of Justin Martyr)

In this passage, Justin uses pagan beliefs to show the eternality of the soul. He cites practices such as necromancy and spirits on earth as evidence that souls after death don’t cease to exist or to be conscious, as some in his day argued. Orthodox theologians see the eternally conscious soul as the main view of the church throughout history.

What Is Soul Sleep and How Does it Relate to the Intermediate State?

Soul sleep is the idea that souls are not conscious after death, but rather go into a sleeping state until the day of judgment and resurrection. Proponents of this view cite Paul’s words in 1 Thessalonians, where he refers to those who died before Jesus’ return as having “fallen asleep.”

Many great Christian thinkers have refuted this view. John Calvin wrote his first book on this topic, Psychopannychia (The Greek word for “Fallen Asleep”). A frequently cited retort to this viewpoint is Luke 22:42. Today in this case means that the we will be united with Christ immediately upon our death.

Why Is the Intermediate State ‘Intermediate’?

Many believers have a false idea that the intermediate state will last forever. We will not be spirit beings in heaven forever. The vision of eternity as one in the clouds is not found in scripture. One day our bodies will be resurrected as well. This is the hope and conclusion of the book of Revelation. The new heavens and the new earth will be perfect. Eden will be recreated in the new earth, and God’s story will be complete and perfect forever, just as it began.

This view likely stems from a gnostic and platonic idea that the body is less valuable and pure than the spirit. There is no evidence for this in scripture. In fact, scripture attributes human’s souls as the reason for their death.

Ben Reichert works with college students in New Zealand. He graduated from Iowa State in 2019 with degrees in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, and agronomy. He is passionate about church history, theology, and having people walk with Jesus. When not working or writing you can find him running or hiking in the beautiful New Zealand Bush.

This article is part of our Christian Terms catalog, exploring words and phrases of Christian theology and history. Here are some of our most popular articles covering Christian terms to help your journey of knowledge and faith:

Categories: Articles, Eschatology

Leave a comment